I finally started reading the actual text–not the images or the commentary by the editor–in depth psychologist C.G. Jung’s Red Book. The first part is called the Liber Primus, which is Latin for First Book. I had been lucky a few weeks prior to watch a webcast of a seminar about The Red Book by Jungian analyst Murray Stein. That brought the material alive to me in a new way, and I’ve read a few sections now.

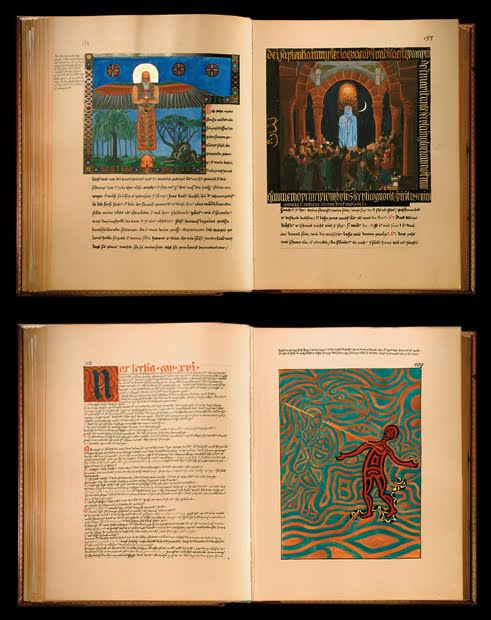

The Red Book is a big folio-sized volume full of visionary paintings and writings that Jung created during a difficult period in his personal and professional life. Over time he put the images and words together in a large red volume, whose blank pages he filled up with evidence of the quest to discover and embrace his own soul, which had become lost to him at that stage in life.

In the foment of his images and imaginative writings, so much is contained of what he elaborated over the years in his depth psychology. Here in The Red Book, his discoveries are in a kind of mythic or visionary form. In his scholarly and popular works, he teases out the meanings and implications of these same discoveries.

No doubt the publication of The Red Book, which for decades has been kept out of public view, will call attention to the roots of Jung’s psychology in his own experiences of the psyche–in himself, in the world, in the consulting room, in world mythologies, and in relationships with others. These roots are rather embarrassing to the modern way of thinking, which is so biased towards the methods of the natural sciences, and the statistical sciences. But the psyche–literally, the soul–has its own reality, to which anyone can pay attention, experience directly, make meaning of, and even elaborate in the form of psychological theory, in the case of Jung as the author of a depth psychology.

Jung often emphasized his scientific credentials and the empirical evidence that backed up his theories. He recognized that his psychology might not find its place in the world of psychology, psychiatry, and psychoanalysis, if others categorized him as a mystic (which they did anyway), who turned to the imagination and soul rather than to science and its methods. His thinking is oriented both to the inward, imaginative, artistic, poetic, and mythical, on the one hand, and to the empirical and scientific on the other. To put it another way: He investigates the soul’s landscape in a disciplined, methodical way, but with room for the soul’s fluidity. A method of discovery should match the object of the inquiry–in this case, the psyche itself, which is naturally in flux, always changing, and charged with deep emotion and powerful images and dreams.

In the images and stories of The Red Book, we discover the rich ore from which a life’s work came. The creation of a psychology and a body of written work began here, in large part, with intensely felt experiences and an attempt to grapple with them in word and image. The material is archetypal, but it is also deeply personal and reflects Jung’s own suffering.

In a section that I found very moving, Jung has a conversation with his soul. The two of them, Jung and his soul, got separated long ago, and the desire to reunite is intense. I will save the details for a later post, but it must be this desire that compelled Jung to return to his own foundations, and to the processes moving forward in his own experience of the psyche.